Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and Goodfellas are two of the most important films in his filmography. Goodfellas, in particular, is considered to be a modern take on the gangster movie tradition and a bold departure from established genre conventions. The film’s unique narrative and characterization betrays audience expectations and focuses on realistically depicting the chaos of life. With this film, Scorsese expanded the gangster genre, established his own distinctive style, and showed himself to be a true auteur.

Imagine Scorsese’s filmography without Taxi Driver. I can’t. To this day, Taxi Driver is still the movie I think of when I think of Scorsese. On the other hand, it’s just as hard to imagine Scorsese’s filmography without Goodfellas. “Ah, Goodfellas, what a great movie. I’ve seen it twenty times over. Um, but is it really that great, especially when there’s The Godfather?”

Some might even put it in a higher class than The Godfather. Considering the movie’s influence, this doesn’t seem unreasonable. In fact, every gangster movie since Goodfellas has been influenced by it, and it’s still frequently on cinephiles’ top ten lists of all time.

The movie is usually considered a modern take on the traditions of the gangster genre. It’s an old cliché, but it’s true. After this movie, gangsters in gangster movies couldn’t be depicted like the Corleone family in The Godfather. It’s hard to see them in strict black-and-white contrasts, sitting in giant chairs obscured by shadows, petting their cats, puffing on bowls of cigarettes, and making their enemies irresistible offers in a cultured voice. We know now that that world is demonstrably false.

The biggest trap we fall into at the same time is that by evaluating this movie only within the traditions of the genre, we miss out on what else is great about it, or we focus so much on its historical significance that we miss out on the pure pleasure of the genre.

I’m going to look at this movie as it is. Or, more precisely, I’m going to approach the movie as it is, bare and untooled, as far removed as possible from the influence of prior criticism and its historical significance, and I’m going to gently pick it up like a young puppy and then put it down. The original purpose of this article is genre criticism, so that’s definitely the direction I’m going in. But I’m not going to dogmatically overstate the movie’s genre characteristics. I want to watch this movie again, 34 years after it came out, purely through my own eyes.

A bold deconstruction of established genre traditions

Henry Hill is Irish. The significance of this lineage is a little sad. Only pure Italian blood can make you a real member of the mafia family. The protagonist, Henry Hill, can’t fit into the mainstream of the mafia, no matter how high he rises. Henry Hill is an outsider in the mafia, but he dreams of becoming a mafioso since he was a child, and it seems natural for him to become a mafioso in the environment in which he was born and raised. Henry’s dreams are translated into his own narrative.

This narration is the first thing that distinguishes this movie from other gangster genre movies. Most other gangster movies have no or little narration. The main purpose of narration is to “tell” the story. The main purpose of a gangster movie is to show the audience a world that is abnormal and despicable. This world is different from the normal world in which the audience lives, and it is depicted not through language, but through lucid vision. In other words, it is not intended to tell a story through language. Therefore, most elements of the gangster genre serve to depict that world.

Goodfellas deviates from this. In this movie, the narrator and the screen play different roles. Henry’s narration is always talkative. He’s constantly talking about how despicable and pathetic the mafia world he’s in is. At the same time, the screen is always showing a different situation. Sure, it’s a different story that fits the narrator’s context. But it’s not the story that the narrator is telling. This is where the movie becomes incredibly rich. The narrative is not simultaneously visualized with the story it is telling, but with another story in the same context. The synergistic effect of these two different narratives deepens the richness of the story many times over. This narrative is a very clever choice by director Scorsese and screenwriter Nicolas Pileggi.

The second feature is the characters, who don’t fit into any of the existing gangster genre subgenres or individual movie adaptations. Most of the characters in gangster movies since The Godfather have been thoroughly and meticulously formulaic. They are all first-generation Italian immigrants or descendants of first-generation immigrants. The men are in charge of the gangster business, but there is a strong female presence in the family. They are strictly kinship-based and live primarily on the blood of others, but will not hesitate to harass their fellow Italians if necessary. Most of them have connections to corrupt cops and are unknowingly protected by the police. And if necessary, they can send “anyone” away quietly. Their killing skills are unprofessional. Backstabbing betrayals are commonplace. Above all, they don’t talk too much, they try to maintain their gangster dignity whenever possible, and they always treat the business as a professional one.

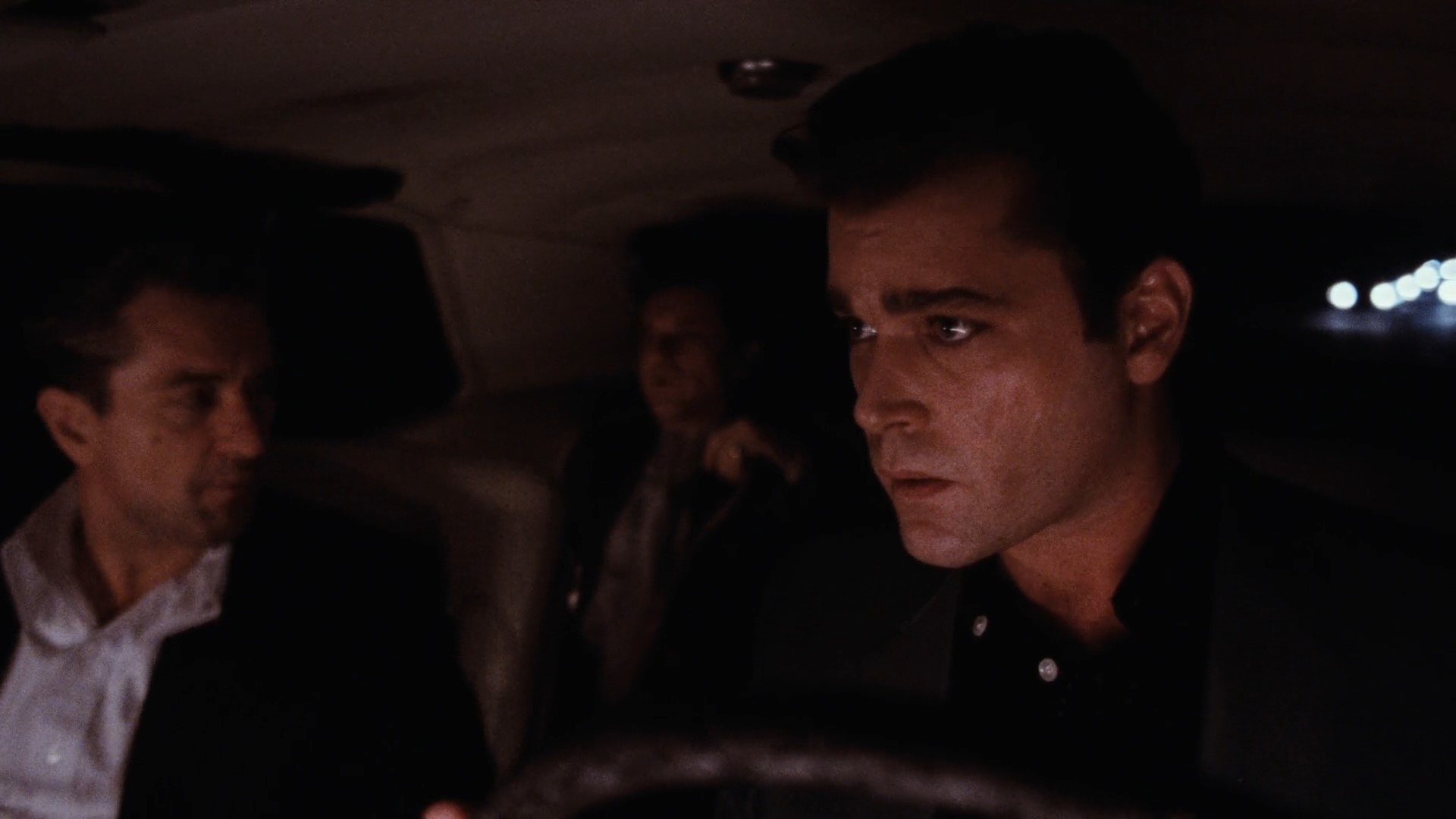

Goodfellas subverts all of these conventional gangster formulas. The Italian organization that Henry works for is mean, lecherous, and stupid. So much so, in fact, that you have to wonder if any of the characters in this movie are thinking. Henry, the main character, is the only one with a shred of sanity in this movie. Jimmy is smart, but he has no sense of morality. Jimmy is constantly, creatively, and consistently getting away with all sorts of bad things. Tommy is an almost semi-maniacal character with an obvious anger management disorder. You never know when he’s going to explode into a rage and put a bullet in someone’s body for no reason. Paul Sisro, the boss of the organization, is perhaps the only character who fits the conventions of the gangster genre. Paul is a man of few words. He doesn’t seem to give much direction, but he’s flexible enough to keep the whole organization running smoothly and coherently.

All of these characters have their place in the narrative, exuding their own solid presence. Compared to traditional gangster movies, the cast of characters in this movie is a bit more messy, for worse, and a bit more polyphonic, for better. And it is in this chaotic and polyphonic composition that the real gangsters are revealed, stripped of their fictionalized aura.

The biggest weakness of this kind of realistic portrayal is that it betrays the conventions of the genre, but it also betrays the expectations of the audience. Most audiences go into a genre movie knowing the basic conventions of the genre. Even if they don’t, they have some assumptions and expectations that this is a movie of this genre, so it will be like this. Goodfellas doesn’t fulfill any of these assumptions and expectations. There is not a single gunshot in the movie, which is a staple of gangster movies. What’s more important than the gunplay in this movie is the chatter between the characters. The movie isn’t interested in creating the cool aura of gangs, it’s entirely focused on how realistically it depicts the dirty world of the streets and how the characters are able to bring their personalities to life.

People without will

Every artist in the world always goes back to what he originally wanted to say, the seed idea. This means that his style changes and evolves over time, but his original subject matter is always the same. Let’s take a look at Scorsese’s filmography based on this assumption. What was the subject of his early masterpiece, A Mean Streets? Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and the surprisingly neglected Aviator? Charlie, the protagonist of A Mean Streets, is torn between the worlds of crime and religion and dies a miserable, bitter death, unable to find his way back to life. Charlie knows that his path is the path of death, but he is unable to overcome his natural temperament and environment, and he walks directly into the path of death and implosion. Travis, the most famous megalomaniacal protagonist in movie history, becomes a hero in a dead end of his own making and oxidizes spectacularly. So does the protagonist of Raging Bull, and so does Howard Hughes in Aviator. Howard Hughes, the protagonist of Raging Bull and Aviator, rots and decays in his mansion, clutching and embracing his severe OCD until the end.

In this way, Scorsese’s protagonists all voluntarily follow a path of destruction. They have enough intuition to realize that their path is wrong, but they don’t have the will to change it.

In this sense, watching Scorsese’s characters is a bit like reading a naturalistic novel by Emile Zola. In fact, it’s similar. Here is a human being. Everything about their lives has been rigorously preordained for them by biological and environmental factors. And these are the most characteristic features of Scorsese’s films, but also the most characteristic conventions of the gangster genre. In this sense, Scorsese has always been a gangster.

“Smart guys with no will”. Henry Hill, the protagonist of “Goodfellas”, is no different. Not all poor Irish immigrants fall into bad ways. Henry doesn’t rebel against the basic circumstances and temperament he was born with. He enters the pre-prepared path without resistance and then takes it step by step. He starts at the very bottom of the organization, doing all sorts of odd jobs, and when he gets a little older, he starts dabbling in the distribution of goods, and when he gets older and more experienced, he gets involved in the business himself.

Henry’s business gets bigger and bigger, and when he goes to jail, he tries his hand at drug trafficking. The drugs bring in a lot of money, but the risks are too great. Henry’s previous work has been petty theft, but drugs are the equivalent of creating your own currency. Paul, the organization’s boss, has a stern warning. Don’t try to trick me and stop now. Henry is undeterred. And when it all comes to an end and he’s caught by the DEA, he blurts out all of the organization’s secrets to the police and is destroyed along with the entire mafia organization. Technically, he’s not completely destroyed as a human being. While other mobsters spend the rest of their lives in prison, Henry is allowed to live like a normal human being after going through a witness protection program. He’s given one more chance. It’s a very un-Scorsese ending: life gives you one more chance. Oh, and the movie’s screenplay is based on a true story. In that case, this ending makes sense.

The End Can’t Be the End

Let’s look at the story of this movie. The story of this movie follows one of the biggest tenets of Scorsese’s movies (not all of his movies, of course). That is, there is no main plot. There is a plot if the previous episode is related to the next, and if it produces some kind of effect. And that’s what most gangster movies are all about. This is because some of the genre’s greatest pleasures come from subtly tweaking pre-existing plots to suit the individual movie. Goodfellas goes in the opposite direction. It has no intention of producing this effect, and the episodes aren’t even connected to each other beforehand. In fact, this juxtaposition of episodes is often the defining characteristic of art films that we call art house.

Wait, is Scorsese an art filmmaker? While Scorsese has admitted to being heavily influenced by European art cinema with its nouvelle vague, it’s hard to categorize his films as art films. Scorsese’s auteurist leanings, coupled with his position on the periphery of Hollywood, make his films difficult to categorize. Scorsese is not a Hollywood B-movie director, nor is he a blockbuster director. His willingness to overtly impose his own point of view on his films suggests that he is as much an auteurist as anyone else, but his films are often shells of genre or history, making it difficult to find a coherent point of view (there are some themes that Scorsese has pursued consistently, such as the life of Italian immigrants). But he is clearly a writer nonetheless. Most importantly, he tries to portray human life as it is, with a transparent eye.

By listing episodes, he rejects the idea that the protagonist’s life is moving towards a single goal. All the events of the protagonist’s life are scattered, based on centrifugal forces, rather than rushing toward a single centripetal point created by the author’s will. And these scattered episodes are not all collected at once in a dramatic reversal at the end of the movie; each episode is self-contained and self-contained. It doesn’t need the other episodes to exist, it can stand alone.

Let’s take Tommy’s “Tell Me How I’m Funny” scene, the most talked about scene in the movie. This scene shows Tommy’s volatile nature and how in the mafia world, you can be shot at any time for the smallest of incidents. The scene begins with a story about Tommy himself robbing a bank and ends with him playfully lunging at the protagonist, Henry. This is followed immediately by a scene in which a restaurant owner, who has been bullied by Tommy, complains to his boss, Paul. These two scenes have Tommy in common, but the stories are separate. The latter scene ends with Tommy and Henry burning down the restaurant. These two scenes are only connected by the element of the passage of time. If you ignore this element and reverse the before and after of the scene, the essential story of each scene is not harmed. And most of the scenes in this movie are stitched together like this. Other gangster movies don’t stitch cuts together like this.

At the end of the movie, Henry picks up the newspaper on his front doorstep, looks directly at the camera, flashes a crooked smile, walks into the house, and closes the front door. We know that Henry will continue to live, but we don’t know how. The movie ends abruptly, but Henry’s life doesn’t end. It’s not the ending we expect from a typical Hollywood movie. We, the average moviegoer, always expect a definitive ending. The episodes need to be connected, even if only tangentially, and there needs to be a sense of continuity, while at the same time racing toward a conclusion. And at the end, it should end the chain of episodes, but it should also have a definite closure, and it should emotionally resonate with the audience in some way. Scorsese’s movie betrays these audience expectations.

Again (always?), it’s about life

This is actually more like our real lives. Our lives don’t play out like a plot, with each event placed in the right place for a distinct effect; they’re disorganized and chaotic, with main plots and subplots scattered in a dizzying array. We can’t see the lives of those around us clearly. Heck, we can’t even see our own lives clearly. We desperately try to make sense of life, but we always fall short of understanding it completely, and so do Scorsese’s movies.

Going back to the parallel structure, each of the parallel episodes does not claim dominance over the others. Because they don’t assert dominance, they all have the same value or different values at the same time. In this situation, it is difficult to make a value judgment about which of the episodes has more impact on the protagonist’s life.

Furthermore, I don’t think Scorsese is judging the protagonist’s life itself. I find it difficult to judge the value of the protagonist’s life in every Scorsese movie I’ve seen, let alone this one. Scorsese’s protagonists are grumpy assholes and subhuman bastards, but they’re also always essentially good people. Can we judge the value of our own lives? There is no superiority between the life of Obama, the President of the United States, and the life of an old man who picks up trash. The value of a life is proven by the process of its creation, and we are the only ones who can judge our own lives.

Scorsese is both a Hollywood outsider and an authentic auteur, in that his films are consistently and intensely human in their questions and answers. Oh, and he’s also a genre filmmaker.

Again, genre.

This movie is clearly a gangster movie. There’s no doubt that this movie is derived from the previous gangster movies, as it borrows and appropriates ready-made formulas. Most importantly, it follows the conventions of the gangster movie in that it depicts the rise and fall of a generation of immigrants serving in the underworld. Furthermore, the movie subverts many of these conventions to varying degrees. In addition to the points mentioned in the article above, there are many small shots and even small camera movements that take the movie in a different direction from the conventional gangster movie.

Taking a step back and looking at the bigger picture, it seems that Scorsese was either borrowing the look of the gangster genre and expanding on it, or he was trying to create his own gangster genre. If you hold a magnifying glass up to the movie and look closely, you’ll see a wealth of camera techniques borrowed from traditional cinema, and if you pay attention to the way scenes are stitched together and the ambiguous ending, you’ll see the art house aspect of the movie. But most audiences who see this movie feel like they’ve seen a great gangster movie. Isn’t that what Scorsese was trying to do, to meld all of these different intentions and techniques into one big framework of the gangster genre?

I’m a blog writer. I want to write articles that touch people’s hearts. I love Coca-Cola, coffee, reading and traveling. I hope you find happiness through my writing.

I’m a blog writer. I want to write articles that touch people’s hearts. I love Coca-Cola, coffee, reading and traveling. I hope you find happiness through my writing.